Seattle claims to 'protect' hundreds of trees that were never threatened

K

athy and Dan Robinson’s excitement about their upcoming kitchen renovation turned to puzzlement when Seattle building officials required them to count and measure each tree in their yard and submit a formal report.

The Robinsons wondered: What do our trees have to do with remodeling our kitchen?

The answer emerged months later when the Robinsons learned from a tree-protection advocate that their cedars, pines, and other trees had turned up on a city map showing trees “protected” during the development process.

That map was required under a controversial update of the city’s tree-protection ordinance passed in 2023 by a conflicted City Council — an ordinance that tree-protection advocates decried as a “giveaway” to developers that would scar the leafy canopy of the Emerald City.

Today the Robinsons’ trees are listed among more than 2,000 trees the city classifies as “protected” — without regard to whether the trees ever were actually threatened by development.

All this is significant because Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell boasted when he signed the ordinance that it would “increase protections for over 100,000 trees.”

Meanwhile, the city’s tree canopy — key to building climate resiliency and providing life-preserving shade during deadly heat waves — continues to shrink, putting the city’s goal further out of reach, as of the latest count in 2021. Tree canopy produces numerous health benefits, including reducing diabetes, high blood pressure and asthma.

The fact that the city is counting so many unthreatened trees as “protected” came to light in a 2024 analysis by volunteers for Tree Action Seattle that verified the trees’ actual status.

RELATED: Seattle passed a tree protection law last year. So why did a 'protected' cedar get the ax?

City officials have long been aware of the discrepancy. In June, a city official acknowledged to the city-appointed Urban Forestry Commission that “the protected trees category, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the code required the tree to be protected.”

“We started digging into the data, and we found that the trees they claimed to be protected were not being protected,” said Sandy Shettler, of Tree Action Seattle. “And so there is no evidence the ordinance is working. In fact, there is evidence it is not.”

As little as 3% of the trees the city said in its database were protected were actually preserved as a result of the ordinance, the group’s study of the ordinance’s early results showed. Also, some trees listed as “protected” on the map already had been cut down.

The city’s Department of Construction and Inspections denied InvestigateWest’s repeated requests to interview Christy Carr, the city official who admitted publicly in June that many of the trees in question aren’t actually “protected” by the ordinance.

When InvestigateWest sought to interview Carr, department spokesman Bryan Stevens requested a list of questions to be discussed “so we can determine who is best to respond.” However, Stevens never authorized any interview — with Carr or any other city official. Instead, in his response to nine questions submitted by InvestigateWest, Stevens sent a 799-word statement that failed to directly answer any of the questions.

“The trees documented on (construction or renovation) plans and not approved for removal are regulated and protected as shown on the public map,” Stevens wrote. “Even if some retained trees are not required to be preserved by code, they are not being removed as part of approved development activity.”

How does that translate on the ground?

Take homeowner Jim Jorgenson, who treasures three now-towering Douglas firs he planted at his house near Green Lake a quarter-century ago. In 2023 he sought city permits to put a partial second story onto the home.

The veteran architect he hired for the job, with decades of experience in Seattle, told Jorgenson about a curious new requirement from the city to count his trees and report back to the city.

Jorgenson and the architect wondered about this new prerequisite.

“We weren’t changing the footprint of the house,” Jorgenson said. “I thought it really odd.”

The meaning of ‘protection’

Retired Boeing engineer and Tree Action Seattle volunteer Dave Gloger heard last spring that a new online city map was tracking what happens to trees during the development process.

Gloger was curious to see 15 trees listed as “protected” at a house just down the street, where he had witnessed no construction activity. Gloger’s wife, Meegan McKiernan, had a passing acquaintance with the couple living there. That couple turned out to be Dan and Kathy Robinson. Gloger stopped by to inquire. He found Dan Robinson out in his garden.

RELATED: Does Seattle’s tree protection ordinance protect developers more than trees?

“They said it was a hassle for them, but they didn’t even know the city was claiming they were protected,” Gloger said.

His curiosity piqued, Gloger looked again at the city’s online map. He saw six other properties in his general area listed as sites of “protected” trees. So he hopped into his Honda Fit and set out for the nearest one. It took only a few hours to drive by all of them.

At a commercial site where buildings had been demolished, 10 trees remained. They were virtually certain to be leveled when the new development began, yet they were classified as “protected,” Gloger noted.

Gloger also discovered a home on a large property in northwest Seattle atop a tree-covered bluff that slopes down to Puget Sound. The small addition going onto the house did not threaten any trees on the property, as the contractor confirmed when Gloger returned to the construction site in November with an InvestigateWest reporter.

Still, the city’s database listed 55 trees on the property as “protected.”

Later Gloger found a house where a wheelchair ramp had been added in front of a house. Five trees near the back property line were still listed as “protected.” “They’re protected because the owners didn’t want to cut their trees down,” Gloger said. “They never asked to have the trees removed.”

He consulted with Shettler, who suggested checking into what was happening citywide. They recruited a handful of other Tree Action Seattle volunteers.

The volunteers reviewed 68 properties, poring over city documents, often focusing on a required arborist’s report. They ascertained what kind of work had been authorized and where that work was located in relation to the “protected” trees. In a few cases where they found ambiguities, they checked with a Department of Construction and Inspections help desk for clarification on what the department had permitted.

The bottom line: “It’s a fallacy that they are protecting trees on properties with construction,” Gloger said. “When SDCI has issued a permit for a property, no matter what (the work permitted) was, if there was a tree on that property, they contended they protected it.”

Of the 341 “protected” trees that the group reviewed in late spring and early summer:

- 100 trees grew on properties where the work involved interior renovations, such as the Robinsons’ kitchen renovation.

- 149 trees stood where some work was authorized outdoors — but the work never threatened the trees.

- 67 trees were actually authorized for removal, even though they came up as “protected” in the city’s online map and database.

- 15 trees stood on sites cleared for future construction, meaning they were still very much in the path of the bulldozer.

- 10 trees had been truly protected from construction under the terms of the controversial new tree ordinance.

In other words, less than 3% of the trees classified in the city’s database as “protected” had actually been preserved under the terms of the tree ordinance on the properties checked in Tree Action Seattle’s mid-2024 study.

The analysis also showed that some other trees listed by the city as “protected” had already been cut down.

Perhaps the most well-known example of this happened after Tree Action Seattle’s study was finished. In the fall, tree-protection activists sought to save a century-old, 4-foot-wide cedar they nicknamed “Astra.” It was felled in October, as reported by Axios. But a check of the city’s map on Jan. 16 showed “Astra” still was listed as “protected.”

Gloger said at the outset of the group’s research, “I thought I’d find a handful of cases. I didn’t realize 97 percent of the cases would be lies.”

Gloger acknowledges that selection of sites to drill down on was not a scientifically random selection process. Different volunteers checked out certain sections of town, often those close to them. But they covered a lot of ground: Of the approximately 900 trees classified as “protected” in the city’s database at the time, the group checked more than one-third.

“We weren’t cherry-picking,” Gloger said.

A little more than a month after Tree Action Seattle released the results of its study, Department of Construction and Inspections Director Nathan Torgelson told members of the City Council’s Land Use Committee in an Aug. 9, 2024 memo: “The permit tree tracking data tells us that more trees are being protected and planted than are being removed.”

Yet, in a passage in the memo defining “protected trees,” Torgelson acknowledged: “These trees are designated to be protected during construction; however, they may not be required to be protected by the tree-protection code or other development standards.”

It turns out that all the city usually means when it lists a tree as “protected” is that during the construction process it had to be fenced off and 8½-by-11-inch “protection” signs placed on it.

The number of “protected” trees in the city’s database continues to grow, even though there is no guarantee of future protection. It currently stands at just over 2,000.

Growing urgency

By the time the City Council passed the new tree ordinance in spring 2023, it was officially 13 years overdue.

Back in 2009, the council had passed an “interim” ordinance, telling city departments to forge plans for a tougher tree-protection law. Next year we’ll pass something stronger, they said. But they didn’t.

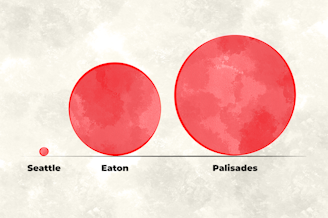

In the ensuing decade, the city’s tree canopy shrank amid an expansion of Amazon that brought more than 40,000 new workers to a city of 610,000. Other tech firms went on hiring sprees, too. From 2010 to 2020, Seattle was the fastest-growing major U.S. city.

It took until 2022 for the council to craft a serious proposal for a new ordinance.

The developers’ lobbying group, the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties, or MBAKS, appealed the proposed ordinance. That legal challenge failed, but even so, city officials sought to find ways to satisfy the development lobby.

Previous InvestigateWest reporting shows that one person involved in winning approval for the ordinance was Marco Lowe, a close adviser to Mayor Harrell who came directly to that job from a position as MBAKS’ chief lobbyist. In his current job, Lowe works closely with the Department of Construction and Inspections, which is funded primarily by fees paid by the development industry and others seeking permits from the department. Lowe did not respond to several messages seeking comment.

The council’s 8-1 approval of the new ordinance came over the objections of the city’s Urban Forestry Commission, which is appointed by the mayor and council and holds expertise in fields including urban ecology, public health and biology.

The Urban Forestry Commission called the approval process “flawed and rushed” and unsuccessfully asked for a few months to dissect the proposal and provide robust feedback.

Harrell, through a spokesperson, declined InvestigateWest’s request for an interview about the Tree Action Seattle study. But asked in an interview with KUOW that aired on Jan. 13 about how to balance the need for new housing with protecting quality of life, Harrell said:

“We took it upon ourselves to talk about tree canopy and tree growth and tree preservation at a time where these are difficult conversations. But to me that goes to the livability and climate change and environmental sustainability. So you have a mayor and department heads that understand there is a balance. We want Seattle to be a thriving Emerald City.”

Tree-protection advocates say Harrell seems to be suddenly whistling a new tune.

“His words don’t jibe with what he sustained” in approving the tree ordinance, said Shettler, of Tree Action Seattle.

“It sounds like city leaders are finally recognizing our tree crisis and the fact that we’re dismantling our climate resilience infrastructure, because that’s what trees are,” Shettler said.

Tree Action Seattle and other groups working to protect Seattle’s trees are gearing up for proposed changes to Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan. They say the skeleton of the plan already shared with the public would exacerbate the damage done by the 2023 tree-protection ordinance. The council plans to adopt the new plan by late June. A public hearing is scheduled for Feb. 5.

“If indeed the mayor and other city officials see climate resilience and the urban forest as a solution to have livability and be climate resilient, why have they put forward a comp plan that adds hardscape, which is building and pavement, to the area where we have our trees?” Shettler said.

She predicted further tree canopy losses.

“The tree ordinance is the opening volley,” Shettler said, “and the comp plan is the final bomb.”